I’ll read this to you if you click the audio👆🏼

Back in the early days of the pandemic, someone said that one way to protect your mental health when the world outside is off the rails is to find a little corner of your life and control the heck out of it.

Straighten a junk drawer, clean out a closet, tend a garden, alphabetize those CDs you still have for some reason.

Based on the rate of crazy in the outside world right now, my little household should be immaculate. Not so much. But one project I am distracting myself with working on is arranging this Index of my previous writings about autism and caregiving.

This past week, I came across one that I didn’t expect to be so relevant right now—thanks, crazy outside world.

Alerts have been blaring across all of my groups regarding threats to the laws that protect individuals with disabilities from discrimination, and the federal and state funding that supports many of my son’s programs.

So, I’m sharing this piece with you today—it’s about how I learned about the disability rights movement back when my son was just a toddler, before that fight became personal.1

Please see the end of this piece for ways that you can learn more and help protect individuals with disabilities whose rights are at risk.

History Lessons

When my kid was eighteen months old, and we were still a year away from the diagnosis that would give a name to his speech delay, I got a head start on disability awareness through a work project.

In the spring of 2001, I was hired as the project historian for a multimedia theatre production based on the writings and reflections of Sam L., a local 56-year-old man with cerebral palsy.

Born in 1944, Sam grew up during an era of incredible transformation for those with disabilities in this country, and his stories reflected those changes. I was brought on to collect information, photographs, and video clips to provide key historical context for Sam’s story.

Sam’s life experiences revealed a lot about the struggles of living as a quadriplegic man at a time when it was extremely difficult for him to gain access to just about everything. But Sam smiled often, proud of his successes in beating down stereotypes. With humor and a bit of sarcasm, he reveled in telling stories of love and friendships, pets, travels, and family.

Just sitting with Sam, asking about his family photos and hearing his stories in his halting speech or through the use of his keyboard device, he taught me so much that I didn’t even know I didn’t know. This was perhaps the first time I'd taken the opportunity to listen to someone who experienced life so differently from me.

I was enthralled too, during my supporting research, to learn about the development of the disability rights movement—events I'd never really thought about before, and the outcomes of which would ultimately have a direct impact on my son’s life.

Sam talked of how his father left when he was a baby. “See, some people can’t handle having a handicapped child. That’s no secret.” My research revealed that at this time in U.S. history, long-standing negative attitudes and lack of understanding about disability were beginning to be challenged by new advocacy groups, such as United Cerebral Palsy. These groups, established by parents, aimed to combat the fears that kept their loved ones with disabilities from being fully accepted in their communities. Sounds pretty familiar now.

When Sam told of his “homebound” schooling that was the only option for his education as a child, I brought in information about the obstacles to education in the years before the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)) passed in 1975. I didn't know then how much of that law I would know by heart in the years to come.

I searched for photographs of the state institution that Sam's grandparents helped him to avoid, and learned about the campaigns in the 1960s to expose the inhumane conditions at these horrific sites, where people with disabilities lived against their will often in squalor and neglect.

Sam joined the nationwide independent living movement in the 1970s as people with disabilities demanded the right to make their own choices about where they would live and work. Even as he moved from group homes into apartments and shared housing, Sam still had stories of abusive, negligent or outright thieving caregivers.

But, through it all, Sam was resilient:

“I accepted my disability when I was seventeen. A lot of people have something happen to them, end up in a wheelchair and they blame everybody else. But I don't believe in that. Get off your wheels and do something. Some people have others around them to get them a home or a doctor. I had to do it all. I fought to be my own responsible person.” – Sam

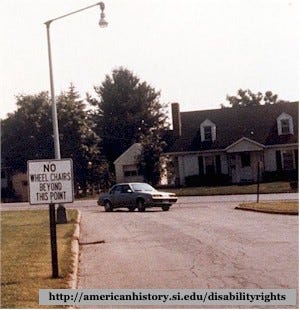

As Sam described years of confronting inaccessible hotels and housing, and limited opportunities for work or career, I placed his experiences in the context of others like him who fought back—demonstrating in protest marches, on foot and on wheels, and literally hammering away at curbs to protest dangerous inaccessibility on community streets.

Sam was almost thirty years old by the time the first civil rights law for people with disabilities was passed in 1973. In prohibiting federally-funded programs from discriminating against anyone based on their disability, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act recognized that the segregation of people with disabilities was not an inherent consequence of their disability, but was due to discriminatory physical and attitudinal barriers created by society.

Those barriers would not come down without an extended fight. Four years later, with that law still not put into practice, disability activists staged a dramatic 25-day sit-in in San Francisco to demand Section 504’s delayed implementation.

As I read about this “other” American civil rights movement, I couldn’t believe that I knew next to nothing about these important, life-changing events, most of which had taken place during my lifetime.

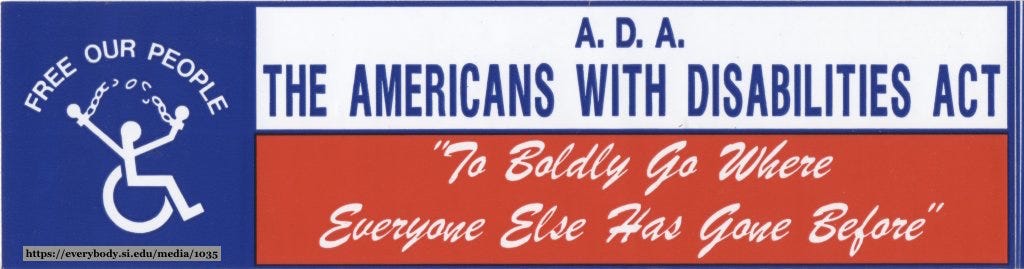

The ground-breaking Americans with Disabilities Act was signed in 1990, following years of battles against discrimination in housing, transportation, medical care, education and employment. The ADA mandates accessibility and “reasonable accommodation” on the federal, state and local level.

This is truly a great American civil rights story. And, of course, the fight to ensure access, awareness, and acceptance for all people is still ongoing.

I didn’t yet understand that my son would be a direct beneficiary of this movement.

A year after Sam’s play was produced, the alphabet soup of acronyms that I learned about in my research (IDEA, FAPE, 504, ADA, IEP) began to appear in our family’s lexicon. Perhaps these terms felt a bit less intimidating because of this “preview” I had working on this project. By the time this cause became personal, I already understood something about the muscle and sweat it had taken to secure those rights for my son and others like him.

For more information on disability history, check out these sites:

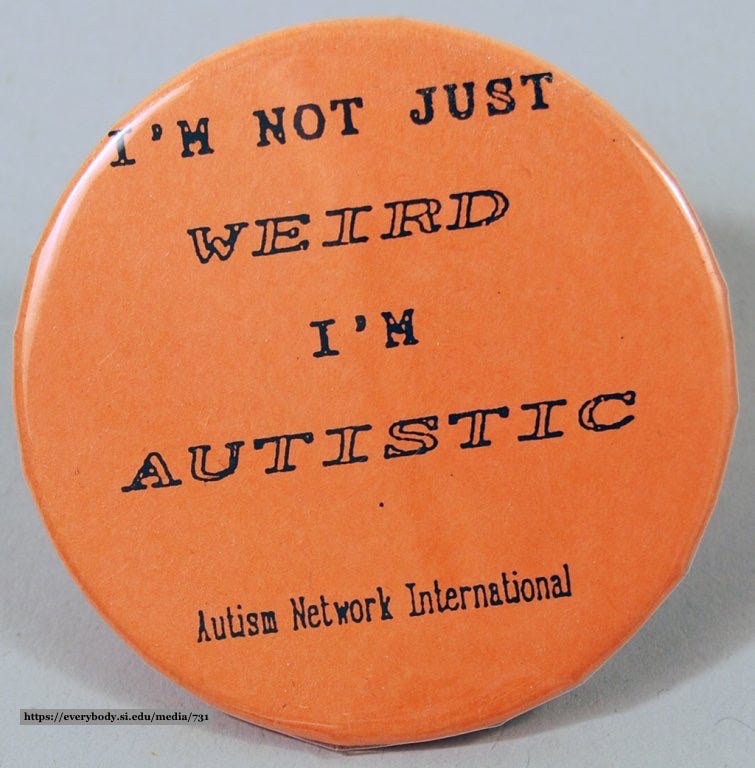

EveryBody: An Artifact History of Disability in America

Parallels in Time by the Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities

TAKE ACTION:

SECTION 504

The current concern is this: Attorneys General of seventeen states are suing the federal government, arguing that Section 504 should be ruled unconstitutional. In 2024, after years of work by disability groups, HHS issued a Final Rule that clarifies and strengthens 504 protections. The Preamble (though not the Rule itself) cited a recent court case which found that “gender dysphoria” may be protected under 504, as an example of a condition that might fit the broadest definition of disability. The states suing didn’t like that, but in their transphobic pearl clutching went further to ask the court to throw out the whole of 504 as too great a burden.

Check out these pages for more info and to easily send a letter to your state’s Attorney General (especially if you live in Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and West Virginia).

This kind of advocacy works because in the last few days, as I’ve been writing this, those AG’s have felt the heat. They’ve submitted an “oops” filing to the court [paraphrased]: “oh, no, we didn’t mean to say all of 504 is unconstitutional, despite using those exact words in our lawsuit. We’ll rewrite it.” So, we’ll see what they present to the court in the coming days. In the meantime:

READ THIS: “A Lawsuit Threatens the Disability Protections I’ve Known All My Life,” by Rebekah Taussig

This is a fantastic article on the history of the 504 and the potential impact of the current lawsuits for people living with disabilities today. Old arguments against 504 that devalue individuals with disabilities and disregard their right to equal access are resurfacing in almost identical language. Taussig says:

“How is it possible that so many people in power seem to have such stunted imaginations, so little curiosity for how to build this world to include more of us?”

But, wait! There’s more!

MEDICAID

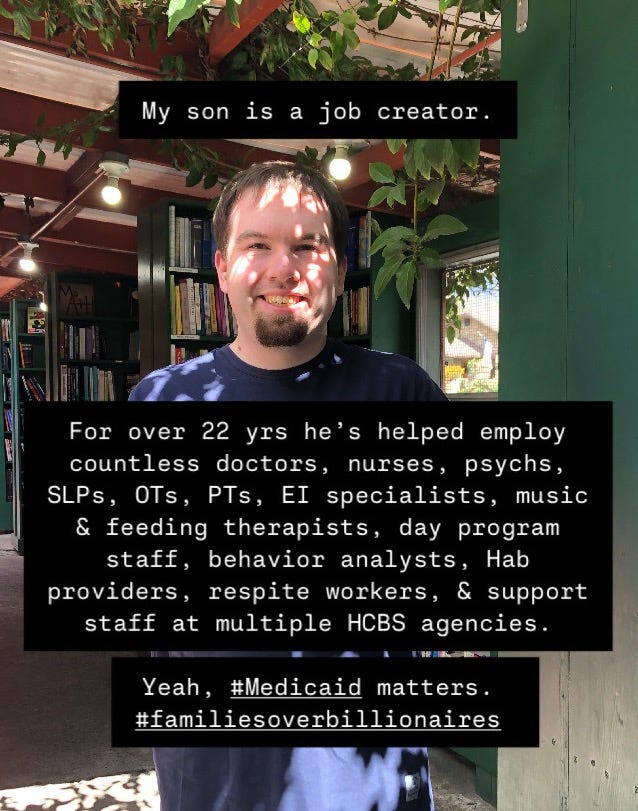

When people see our son out in the community—exercising at the park, buying treats at Safeway, or spinning his beads through Goodwill—we often hear, “Wow, he is doing so good!”

He is doing well—thanks to Arizona’s Medicaid system.

Medicaid—for home and community based services like speech therapy and day programs; for health insurance and prescriptions; for behavioral health services—has been vital to our son’s health and wellbeing. It is not a perfect system, and reform to ensure that Medicaid works “for the most vulnerable” (as the House budget resolution states) is complicated. Cuts to Medicaid have the potential to be devastating to millions of people who rely on this program.

Click here to tell your representatives to protect Medicaid:

PUBLIC EDUCATION

Read this for an excellent summary of the current threats to public education and the laws that ensure students with disabilities across our country have access to a free and appropriate public education. See if your representatives are sponsoring the latest bill to dismantle the Department of Education, and make some calls if you can!

Thanks, as always, for being here. You may now go back to your favorite personal distraction.

This piece first appeared on my blog in April 2016, as part of a series in honor of Autism Awareness Month. At the time, I noted: As the parent of an autistic teenager, it’s hard to remember a time when I wasn’t “aware” of autism, since it is such an integral part of our everyday life. But there was a time – in fact, the majority of my life – when I did not know anything about autism. Throughout April, I’ll be sharing a few moments from the months and years just prior to my son’s diagnosis, when the pieces of the "awareness" puzzle were just clicking into place for me.

This was a great post Robin. One I’m very glad you found in the archives.

I remember when I first heard about the disability rights act and all that those incredible people did to push it through. I haven’t yet, but one of the many ideas I have for upcoming substack pieces is to right about Judy Heuman and her involvement in this movement.

Also, I hope things work out regarding the protection of your sons (and others) rights.

Thank you Robin - I've been a fan of your writing for a long time (and a fan of yours for even longer). This piece really hits me in the feels. 🤗