I’m not saying I’m a better mother because I played one in a high school production of Our Town.

But that’s almost the truth.

Bear with me for a backstory, and I'll try to explain.

***

When I auditioned for Our Town at my high school in the fall of 1988, I had just returned from a summer intensive theatre & dance program, part of the National High School Institute at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Before this, I had been playing around with performing since elementary school, taking dance classes, and acting in a few school plays and community productions.

Below: a double role as a "real" rabbit and a fire truck in The Velveteen Rabbit for a children's theatre. I was 13 and hated that fire truck costume. The rabbit suit I was OK with...?

But this summer program at Northwestern was big to me.

I joined all these hugely talented students from all over the country—budding actors, dancers and singers who had been honing their skills for real, way beyond my small experiences, at least that’s how it seemed to me. Some of my Cherub classmates had family members in the business (I tried to play it cool when we caught sight of Henry Winkler on campus); and a few of them went on to genuine careers in theatre, film or TV. That’s how fish-out-of-water I was—the only student from Arizona and one of the few outside of LA, NY or Chicago.

Over those five weeks, I was cocooned in an atmosphere of creativity and a passion for performing (yes, even at lunch, someone would break out in song). We rode the “L” into Chicago to see incredible shows at the Steppenwolf and other theatres. We met with real working actors who gave us tips and warnings about pursuing a theatre career. We learned from instructors with full theatre, dance and film resumes, including writer-director Peter Hedges, who was at the beginning his impressive career, and would go on to write What’s Eating Gilbert Grape a few years later. The training in voice, movement, dance and acting was intense and challenging, and I left there wanting more.

Below: Mask work with friends; meeting film actress and Chicago-native Jami Gertz; acting coach Peter Hedges; and the Cherubs of 1988, including Noah Wyle (soon to be of ER fame) already standing out from the rest of us at the far right.

I wasn’t the most talented, by far.

But I loved the work.

Coming back to my senior year of high school, I went all-in for drama. I dropped most of my other extracurricular activities to dedicate my time to the stage. I volunteered at a downtown Phoenix theatre as backstage crew for a production of La Cage Aux Folles. And, at school, I auditioned for Our Town.

I had my sights on the role of Emily, the teenaged lead with the dramatic monologue that closes out the show. The weight of my newly-inspired actor ego was enormous, and I expected that my summer of vocal exercises, mask work and weird improv games would surely put me out ahead of my classmates. So, when I was passed over for the lead, and offered instead the (still hefty) role as Mrs. Gibbs, I was devastated as only a teenager can be.

I sent a letter to Peter Hedges, lamenting over this insult and confessing that I was at a loss as to how to portray a housewife who’s been married longer than I’d been alive. I was supposed to play the young girl, coming of age, not the apron-wearing mother of two! Peter called me from an airport payphone while waiting for a flight (which did nothing to diffuse my already inflated sense of self-importance), and in his soft-spoken, thoughtful way, talked me back to reality.

Peter reminded me that every role was an opportunity to grow as an actor, that some of the best parts he’d played were supporting ones, and that if I dug deep, I could find a way to play Mrs. Gibbs with authenticity.

I was just starting to learn what actors do to take on a character—the work that’s needed beyond simply memorizing what to say and where to stand. I knew I had to find a meaningful connection to this mother, to genuinely feel how she feels.

Later on in my theatre work, both in and after college, I think I got better at this. As a performer and as a director, I was the nerd who actually enjoyed the tedious “table work” of the early rehearsals, the process by which the cast discovers how the characters feel, the motivations that underlie their interactions, and the personal experiences they can draw from to understand and inhabit the emotions of the scene.

But in my first real attempt at this, as a rookie actor with limited life experience at 17, I somehow decided I could relate to the worries and responsibilities of this turn-of-the-century wife and mother by tapping into my feelings about my dog.

I don’t remember what brilliant analysis I came up with about Mrs. Gibbs' internal life, but I do remember pacing in the darkness backstage, doing some “emotional recall” exercise involving my cockapoo Buffy. If my fellow cast members could tell from my whispered mantras that I was trying to connect emotionally to Mrs. Gibbs through my experience as a dog-mom, they probably thought I was nuts.

I may have been. It doesn’t make much sense to me now—I’m guessing my dog was the closest thing I had at the time to having a maternal relationship with another living being—and I doubt my performance showed the level of effort I was putting into it backstage.

But I just loved the work.

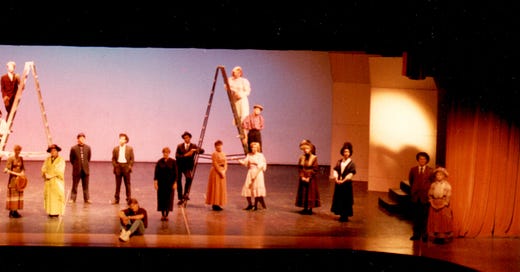

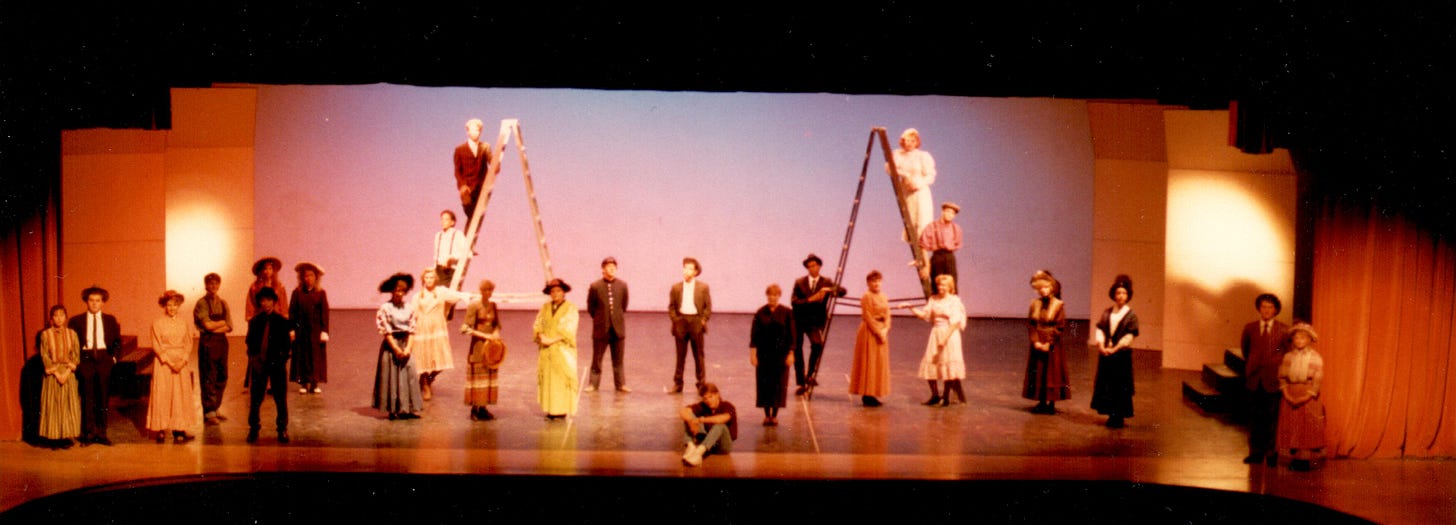

Above: This could be a photo of any high school production of Our Town, but this one is ours, Nov. 1988. I think I'm on the far left.

***

I didn’t get far from Grover’s Corners in my theatre career, but the few years I did spend working on shows in college and in local professional and amateur theatre gave me skills I still use in my off-off-off-Broadway life as a parent.

Not only can I read a bedtime story with full dramatic effect (even a “cold” read), sew a fairly decent Halloween costume, use a cordless drill, and appear smart in certain categories of Jeopardy!,

I can also use those old character analysis skills to try to relate to how my son feels, even if I’ve never been “in his shoes.” It’s a useful skill for someone who is not autistic raising a son who is.

When my son needs to return the salt & pepper shakers to the exact center of the table immediately after anyone uses them, he will often hear my exasperated sigh.

But if I remember that the uncomfortableness he feels when those items are out of place might be like the tension I feel when someone has left the toilet seat up, I can empathize.

When my son needs extra time to sit in the car when we arrive at our destination, he might hear a lecture from me about time management.

But if I remember that, in unfortunate opposition, the anxiety he feels when transitioning between activities is probably similar to the stress I feel when I’m running late, I can empathize. We can practice deep breathing techniques together.

It’s ok that I wouldn’t react the same way as my son to an errant salt shaker or an impending transition. Just like my teenaged self didn’t need to have the direct experience of motherhood to understand, in some way, the feelings of a mother who nags her son on his wedding day to wear his galoshes so he won’t “catch his death of cold.”

I just have to recognize the emotions—of unsettledness, of fluttery nerves, of fear, of loss of control—and remember what those feel like in my gut. Then, I can empathize.

My practice of empathy won’t win me any Tony awards (nor will my dramatic bedtime stories).

But I do love the work.

***